I've just finished reading the book Atlas, written by Michel Serres in 1977. Going back over my notes, I'm interested in a sentence on page 66 which reads: “Seeing presupposes an immobile observer, visiting requires that we perceive by moving.” Michel Serres writes this to support a reflection on the near and the far, the interior and the exterior and, finally, on our way of being in these spaces. In particular, he wonders about the wanderer, who is always on the move, and the homebody, who knows his territory through short, habitual trips to his immediate neighbors. He poses his question in the following terms: “Which of the two knows space better […]?" And so, do we necessarily have to travel to get to know space? Or, putting the question differently, which of “seeing” or “visiting” enables us to better perceive our environment?

It may be counterintuitive, but as I read this sentence, Jean Louis Boissier's L'écran comme mobile (The Screen as Mobile), published in 2016, comes to mind. Taking up his research on “relation as form”, questioning interactive movements as methods of writing, the author describes the place of screens - and more specifically smartphones - in these interactive moments.

But above all, he poses his hypothesis as follows: “Doesn't the virtual part of the real that we now carry around with us, with our mobile screens, make us immobile?”

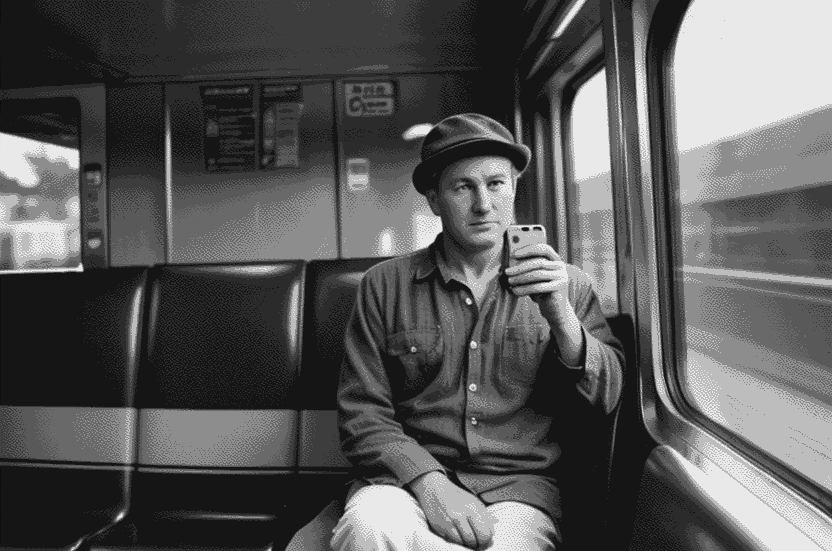

He makes it clear that he doesn't mean “immobile” as a description of beings devoid of all movement, but rather as the name of a new regime of mobility. By analogy, he describes this immobility more or less as that experienced on a train. The body sits in the carriage, a priori immobile, but moves thanks to the vehicle that transports it. Here, the author points out that “the immovables outside ‘ordinary’ mobility that we have just described can illustrate [...] the way that the immobile finds to superimpose itself, or substitute itself, for all kinds of effective mobilities.” This underlines the fact that we are not completely immobile in front of a screen - our bodies no longer move, but we navigate in other spaces.

Let's take another look at Michel Serres' essay in which, a few pages before, he wonders whether there might not be a concept between local and global, something that would link the two? This is where Jean Louis Boissier's “mobilisable” screen comes into its own. Mobilisable refers, in medicine for example, to “to make mobile”, but also to the quality of “mobilization”. For the author, by linking the term “mobilisable” to the screen, we are announcing a performative dimension, i.e. a signifying experience. “Mobilizing a screen means finding mobile content for it, moving images, but it also means making it active as an object, as a support.”

The smartphone user thus moves from “seeing still” to “visiting in motion”, from homebody to wanderer. But perhaps not so much moving from one to the other, as remaining one and the other, a link between the local and the global, a linked and complex understanding of juxtaposed spaces. Without wishing to force links between the two works, written almost forty years apart, I find it interesting how Michel Serres repositioned the two verbs and questioned their relationship to movement in space. This is how he situates his work on being there and being out of there.

But let's go back to the definitions of the two verbs.

To see is “to register the image of what is in the visual field, passively, without prior intention”.

To visit is to go somewhere to see... a place, a person, to be at the bedside of, or to make one's presence known.

The first verb seems to position the body as an immobile point, while the second emphasizes the need to move the body elsewhere.

I'm not so much interested in answering Michel Serres's question about who knows the territory better - the wanderer or the homebody - as in understanding what these postures are in digital spaces. If this blog questions the virtual, it's to define some of its contours. One of these is the place of the body within it.

Without wishing to conclude the discussion here, I'd like to propose a hypothesis: do both profiles exist in digital worlds? From the homebody, who navigates in a controlled, everyday Internet or in familiar virtual universes; to the wanderer, who digs, searches, moves in the bowels of the web to find new resources.

But in certain virtual worlds, such as video games, redundancy (the possibility of returning and replaying a world, even if it's a large one) brings us back to the posture of the homebody. Recognizing places, spaces, places where memories are anchored ... repeating the game, again.

In an interview conducted on February 27, 2025 with a gamer about this type of experience in the video game Grand Theft Auto 3, the interviewee raises two points that move the discussion forward. The first is that he speaks of his relationship with the game's locations “like vacation memories”. The second is that he refers to a certain bodily memory; the player's body remembers, via the interface, his finger gestures as he navigates a space. For example, the physical sensation of driving in the game, the key to open the car door, or - as the interviewee put it - the series of keys hammered to type in cheat codes and escape the police.

To complete the description of our two verbs, the posture described here is complex. It can be about seeing, as the body is motionless in front of the screen. But it's also about visiting worlds, moving in a space to grasp its particularities, or to recall moments of life - real ones. It's a question of becoming immobile, perhaps, of moving on top of a frozen posture. But it's by no means a question of passivity - indeed, the term doesn't seem to fit the act of seeing either.

This text doesn't give a definitive answer to this hypothesis, but proposes to reflect on these postures, as this complexity has caused many misunderstandings, including when defining other terms such as immersion, for example.

Visiting requires perceiving between movement and immobility, seeing without being totally immobile, understanding an environment in which the body is not in substance.

Michel Serres, Atlas, Paris : Ed. Flammarion, 1977, 288 p.

Jean Louis Boissier, L'écran comme mobile, Les Presses du réel, 2016, 240 p.

FIG 01. AI-generated image of a man on a train, looking at his smarthpone