* Important note: this text examines the term “sage/wise” in French and its lexical ambiguity. The English translation of the text may create some approximations or misunderstandings, because in French the term “sage” means both a person with knowledge and a person who respects the rules.

Keep this in mind for the rest of the text, and enjoy your reading!

Wise / Sage

Who has the ability to understand and judge all things fairly (has aged).

One who behaves according to a moral law or conscience.

One who judges, behaves prudently, cautiously.

Whose conduct or behavior is full of moderation; far from excess, free from passion.

Docile, disciplined.

Wisdom shifts. From the knowledge and experience that enable one to judge and react appropriately to a situation, to docility and unconditional respect for religious, political and social rules. The term seems to have appeared in French in 1050, in the Life of Saint Alexis, to designate a “learned and educated” person. Already among the Ancient Greeks, the wise man was one who distinguished himself by his knowledge and erudition. In 1140, Geffrei Gaimar used it in his History of the English to refer to a “just” person. In 1170, Chrétien de Troyes (Grec et Énide) changed the definition of the term, referring to a “wise” young woman, understood here as “reserved”. He also used the term in the Tale of the Grail, but to designate “one who has the right knowledge of things”. The term then took on the meaning of “mastering one's passions”, until the 16th century declension we know today of “behaving oneself”, not being turbulent or capricious. Today, the two definitions coexist, but slip through time: we'd say of a child that he must behave himself, i.e. be disciplined, and of an elder that he is wise, that he has aged enough to obtain knowledge. If I'm stretching this idea, when a government entity tries to soften its population, to keep it disciplined, it's because it considers that its people aren't wise enough, that they don't have the necessary knowledge to be just, in other words that they're behaving like children. I'm extrapolating, but that's the ambiguity of this term and of our subject.

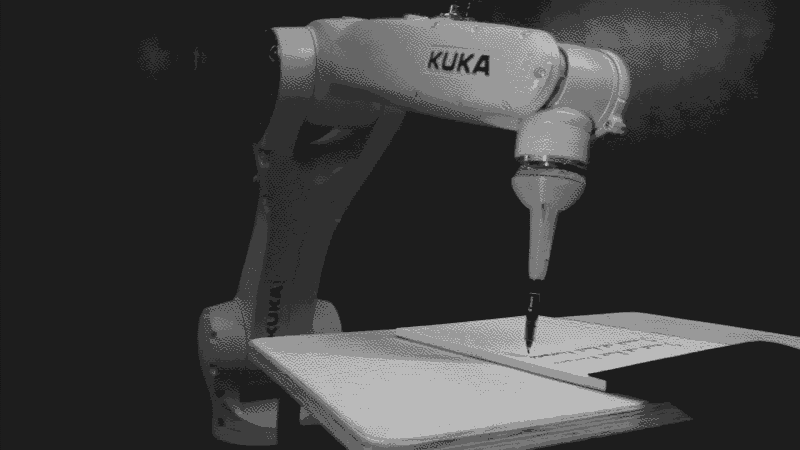

This ambiguity is reflected in the very early stages of parenting. At this stage, the two terms are often confused, between the well-behaved child - who must not deviate from the rule - and the child in apprenticeship. Artist Filipe Vilas-Boas examines this issue in his work The Punishment, an installation consisting of a school table and an orange Kuka robotic arm that writes on a sheet of paper “I must not hurt human” (see Fig. 02). Here, the robot is punished in anticipation of an eventual mistake, like a schoolboy, learning through punishment, knowing the rules it must not exceed.

Virtual spaces, and the web in particular, seem to be at just this tipping point. They lie between spaces of infinite sharing of human knowledge and spaces of systematic control and repression of speech. Artificial intelligence training is a case in point, between the desire to create objects of infinite knowledge and the systematic censorship of subjects. In her book Atlas of AI, Kate Crawford examines this question, analyzing classification as a technical stage in the organization of knowledge in order to train machines, as much as a stage in the seizure of power over knowledge by reorganizing and orienting it. I quote:

« In their landmark study of classification, Geoffrey Bowker and Susan Leigh Star write that "classifications are powerful technologies. Embedded in working infrastructures they become relatively invisible without losing any of their power." Classification is an act of power, be it labeling images in AI training sets, tracking people with facial recognition, or pouring lead shot into skulls. But classifications can disappear, as Bowker and Star observe, "into infrastructure, into habit, into the taken for granted." We can easily forget that the classifications that are casually chosen to shape a technical system can play a dynamic role in shaping the social and material world. » (Atlas of AI, p. 127.)

Using various examples (Amazon and IBM in particular), the author describes how classification becomes a tool for controlling knowledge and bodies. Precisely at the frontier of terminology, so-called AI programs fall somewhere between wisdom, knowledge and control.

In 2019, English artist Jake Elwes begins a new series. He decides to train a facial recognition AI with a new database made up of 1,000 portraits of transgender, genderfluid and drag people. His first result, Zizi - Queering the Dataset (see Fig. 01), led to the creation of the character Zizi, with whom the artist performs between human and AI. This first project, rendered in video format, shows the result of this “queering” attempt, a never-fixed image that shows pieces of faces, people of indefinable genders and constantly shifting shapes and colors. The program struggles to recognize the faces, searching for codes or regularities without ever succeeding. The artist is thus engaged in a struggle against classification and its binarity (gender, but not only), and its effects on our societies, now designed to function solely on the basis of data and its processing.

Zizi represents the bug in the system, anti-classification irregularity and a form of resistance through wise disobedience.

CNRTL, definition of sage, read here

Kate Crawford, Atlas of AI. Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Article Intelligence, New Haven: Yale University Press Book, 2021, 327 p.

Filipe Vilas-Boas, The Punishment, 2017

Jake Elwes, Zizi - Queering the Dataset, 2019

FIG 01. Jake Elwes, Zizi - Queering the Dataset, 2019

FIG 02. Filipe Vilas-Boas, The Punishment, 2017